The Madness of Multiple Choice, A Guest Post by Andrew Pudewa

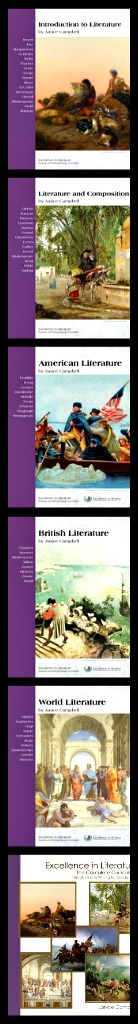

If you’ve ever wondered whether Excellence in Literature needed a few multiple choice questions to make it “better,” this delightful essay by my friend and publisher Andrew Pudewa will make our position clear. Like comprehension questions, another pernicious evil, multiple-choice testing is a blight on the educational process. I hope you enjoy this!

If you’ve ever wondered whether Excellence in Literature needed a few multiple choice questions to make it “better,” this delightful essay by my friend and publisher Andrew Pudewa will make our position clear. Like comprehension questions, another pernicious evil, multiple-choice testing is a blight on the educational process. I hope you enjoy this!

The Madness of Multiple-Choice

by Andrew Pudewa

At some point, one of the hardest decisions that a home-schooling family must make is whether to do “Home Education” or to do “School” at home. Many times this choice is made by default when a family jumps into home-schooling by purchasing a complete “curriculum-in-a-box” (or on a disk), in an attempt to find something that will “cover all the bases.” On the other hand, some families who choose to break free from a “complete” grade-level based pile of textbooks and workbooks feel like they are engaging in something radically different, which they may call “unit study,” or “unschooling,” or “classical,” or any one of several different labeled philosophies or approaches.

Certainly these pioneering families are choosing paths less traveled, but they are doing so in greater and greater numbers. Some do it from the get-go; some begin the journey after years of slogging through worksheets and school books, wondering if there isn’t another, better way. Providing fuel for a change in direction, authors like John Taylor Gatto, Doug Wilson, Marva Collins, Glen Doman, and many others show a glimpse of how things could be different, even providing treasure maps, guidebooks, model classrooms and periodic pep talks. Most parents pursue these possibilities because they have three basic qualities that push them to it: love for their kids, a modicum of confidence, and common sense.

Writing is thinking and workbooks can’t teach thinking

And yet for many other parents, who also possess love and common sense, it can be hard to depart from the broad, safe road of “school-at-home.” The pre-designed lesson plans, the carefully programmed “teacher edition” textbooks, the daily and weekly suggested schedules, the tests with answer keys—in other words, the security of knowing that your fifth grader is doing what other fifth graders are (or should be) doing—these are the things which, for some, make home-schooling a practical possibility, and they hang on to it tenaciously. . . at least until they encounter the task of teaching writing. When parents come face to face with the shortcomings of the workbook approach in this area, they get concerned. They see the child’s frustration. Writing is thinking and workbooks just can’t teach thinking. Understanding the importance of composition as an important life skill, these parents search here and there for yet another workbook or computer program that will do the job, but they seldom find anything that actually works. Why?

Textbooks, workbooks, and “canned” curriculums cannot teach thinking; they can only seek a predictable, “correct” response. Their very existence is based on a multiple-choice fill-in-the-blank, right/wrong system of pushing information into a child’s head. There is no room for different answers, unique responses or independent views. The emphasis is always on what the child doesn’t know, not on helping him clarify and express what he does know. Epitomizing the type of instruction specifically designed to condition the child, multiple-choice tests and right/wrong workbooks can program correct responses, but they cannot teach a child to think.

Being tested on what we didn’t know

I and most everyone I know grew up in this educational culture. We don’t know (and can’t easily imagine) anything different. For the most part, conditioning is what school was (excepting the one or two truly remarkable teachers who may have taken the radical approach of encouraging actual thinking). For us, grades were based on homework and tests, most of which were designed not to test what we did know but specifically to test what we did not know. “Uh, oh… I didn’t know seven things on that test, I’m stupid!” “Johnny got a 100%… he’s so smart, he knows everything! But I’m just dumb. I hate this.”

No, Johnny didn’t know everything, and he wasn’t necessarily any smarter than you or I. He was just good at learning the specific few things the system thought he should learn. You may well have learned countless other things–things that were more interesting or useful to you–but the system didn’t test you on what you did know, only on what you didn’t know. For us, school was an eleven or twelve year conditioning process, slapping us back into line, giving us a common and narrow set of information carefully chosen to make us think predictably and behave controllably, limited in originality and easy to influence economically and politically.

You see, the multiple-choice test mentality is not just stupid, it’s evil. By placing a continuous emphasis on what you don’t know, multiple-choice tests trivialize what you do know. To a multiple-choice test answer key, who you are, what you know, or how you think is irrelevant. But the painful irony of it all is, in truth: it’s what youdon’t know that is actually what’s irrelevant. You’re not going to know everything there is to know about everything anyway, so who cares what you don’t know? What you don’t know isn’t important at all! What is important is what you do know, and that you know that you know, and that you can communicate it effectively. And, by the way, that’s how tests have been done for centuries (the centuries before computers had maliciously promoted multiple-choice). The mentor or teacher would say to the student, “Tell me everything you have learned about what we’ve studied.” The test was to see that you had learned something, not that you had learned the narrow and specific facts prioritized by a particular worldview or sociological system. Real learning and thinking is about what you do know, and knowing that you know it.

Educare — “to draw out”

That’s actually the common sense approach to education. It’s what the word means. Educare – “to draw out.” Instructo, on the other hand, means “to pile upon.” Parents and teachers hit the wall of “instruction” when they begin to teach writing. You can “pile on” and test history facts, math facts, science facts, even religion and spelling facts, but you can’t “pile on” writing instruction. Writing is thinking, and once the tools have been taught, the shift is now to educate, or to “draw out” from the child that which he knows. As I travel and teach writing all over the country, I often meet children who don’t like to write. Now, if you ask a child why they don’t like to write, their most common answer is, of course: “I don’t know what to say.” One of the activities I do with children (after some practice in basic note taking) is an exercise I call “brain inventory,” or just making a list of “things that you know somethingabout.” After listing their dog or cat and their one or two favorite sports, many children can’t think of much else that they “know something about.” They just don’t they feel like they know a whole lot. The fact is, of course, that they do know much more, and with just a little coaching, they can find all sorts of “stuff” in their brain, but they are not used to that type of thinking. They’re used to having a workbook to tell them what they know. When it’s not there, they’re lost. What I do is very new to many kids. It’s a common sense approach, but not a common one in today’s multiple-choice culture.

As if requiring teachers to do more of what hasn’t worked will suddenly improve things

Originating as part of a clandestine effort by the inner sanctum of social scientists in their university halls and corporate board rooms, the madness of the multiple-choice mentality now unabashedly emanates from the most obvious sources of political and economic power—governments and media. Following the states and their legislators in striving for an elusive educational “standard,” our president and congress have hopped on the driverless wagon of national testing, as if requiring teachers to do more of what hasn’t worked will suddenly improve things. And the media, they love multiple-choice. Take, for example, the recent tragedy of terrorism and the “interactive” nature of the television and internet. One major news network gave three choices as possible responses to the question: “How does this terrorist attack make you feel?” Only three options were available: Surprised, Sad, or Angry. Any more complete expression of feeling or detailed response wouldn’t work in their bar chart, so everyone responding to their “interactive experience” was forced into one of three narrow but equally as vague little boxes. I personally couldn’t trim my complex feelings and thoughts to fit into one of those three options, and it seems to me that any thinking person would be equally as offended by the overly simplistic nature of that multiple- choice question. But this is the way children have been, for decades, trained to respond by their textbooks and worksheets.

Now we, as home-schoolers, have some options that other parents don’t have. We can, of course, do “school” at home, obediently following our worksheets and nicely administering our end-of-chapter multiple-choice tests. Or, if we can see outside the box of our own conditioning, choose to do something radically different. We can, right now, make the decision to care more about what our children do know, rather that being worried about what they don’t know. We can determine to draw out real thinking, rather than programming our students with the “correct” textbook responses. We can, if we have the courage, “just say no” to multiple-choice tests, and the whole mentality that goes with it. No, you won’t “cover all the bases.” Your children won’t know everything they’re “supposed to.” They will learn different things than what the other fifth graders are learning, but they may very well learn better how to think, and to know that they know what they know. And if they do the same for their children and grandchildren, we may find in a few generations a large number of people have become more thoughtful, more responsive, more diverse—in other words less controllable and less conditioned—and perhaps a bit more like our founding fathers. And that might be a very good thing for our country and our world.